By

Chris Jones, Statewatch researcher

This is the second in a series of posts examining the EU's Data Retention Directive, which is the subject of today's judgment of the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU). It is based on work undertaken by

Statewatch as part of the

SECILE project (Securing Europe through Counter-terrorism: Impact, Legitimacy and Effectiveness).

The post begins with an article-by-article examination of the Directive and subsequently examines the troubled national transposition and review process overseen by the European Commission. The

first post examined the background to the Directive, and a subsequent, final post will look at national court cases challenging the implementation of the Directive.

The Directive, clause-by-clause

Article 1 sets out the subject matter and scope of the Directive, which covers all legal entities and:

“[A]ims to harmonise Member States’ provisions concerning the obligations of the providers of publicly available electronic communications services or of public communications networks with respect to the retention of certain data which are generated or processed by them, in order to ensure that the data are available for the purpose of the investigation, detection and prosecution of serious crime, as defined by each Member State in its national law.”

Article 1(1) of the Directive states that serious crime is “as defined by each Member State in its national law”. Article 1(2) states that the Directive does not apply to the retention of the content of communications. However, it has

long been argued that “retaining [internet] traffic data makes it possible to reveal… what websites people have visited”, indicating that certain content data can be retained under the Directive. The EU’s Article 29 Working Party on data protection issued an

Opinion in 2008 making clear that the Directive is “not applicable to search engine providers”, as “search queries themselves would be considered content rather than traffic data and the Directive would therefore not justify their retention.”

Article 2 contains definitions. Article 3 outlines the obligation for telecoms providers to retain data, through derogation from a number of Articles (5, 6 and 9) of the

e-Privacy Directive. Article 5 of that Directive obliges Member States to:

“[E]nsure the confidentially of communications and the related traffic data by means of a public communications network and publicly available electronic communications services” through the prohibition, except when legally authorised, of “listening, tapping, storage or other kinds of interception or surveillance.”

Article 6 of the e-Privacy Directive prohibits the retention by telecommunications providers of “traffic data relating to subscribers and users” except if necessary for billing or marketing and with the users' consent. Article 9 states that location data relating to users or subscribers “may only be processed when they are made anonymous, or with the consent of the users of subscribers to the extent and for the duration necessary for the provision of a value added service.”

Article 4 of the Data Retention Directive covers access by Member States’ competent authorities to retained data, which should only occur “in specific cases and in accordance with national law”. The phrase “competent authorities” is undefined in the Directive. Member States decide which of their agencies and institutions can request and access retained data. Member States also define the procedures authorities should follow to get access to retained data. This has led to wide divergence between Member States in which authorities can access retained data, and how they do so. The Directive also fails to stipulate that national law should include judicial scrutiny of requests for retained data, allowing Member States to establish self-regulatory systems that dispense with traditional surveillance “warrants”.

Article 5 lists in detail the data that must be retained by service providers:

The source of a communication;

The destination of a communication;

The date, time and duration of a communication;

The type of a communication;

Users’ communication equipment or what purports to be their equipment; and

The location of mobile communication equipment.

Article 6 covers periods of retention (“not less than six months and not more than two years from the date of the communication”). Article 7 outlines measures for the protection and security of retained data, compliance with which is to be supervised by “one or more public authorities” in accordance with Article 9.

Article 8 states that the storage of retained data must allow for its transmission to competent authorities, when requested, “without undue delay”. Article 10 obliges Member States to provide annual statistics to the Commission.

Article 11 makes an amendment to Article 15 of the e-Privacy Directive, paragraph 1 of which permits Member States to enact their own data retention measures if they consider them:

“[A] necessary, appropriate and proportionate measure within a democratic society to safeguard national security (i.e. State security), defence, public security, and the prevention, investigation, detection and prosecution of criminal offences or of unauthorised use of the electronic communication system.”

The Data Retention Directive supplemented this by stating that: “Paragraph 1 shall not apply to data specifically required by [the Data Retention Directive] to be retained for the purposes referred to in Article 1(1) of that Directive.” This legislative overlap has been problematic and the European Commission, which is reviewing the Data Retention and e-Privacy Directives in parallel, has

suggested that:

“Any revision of the Data Retention Directive should ensure that retained data will be used exclusively for the purposes foreseen in this Directive, and not for other purposes as currently allowed by the e-Privacy Directive.”

Article 12 permits Member States to extend retention for “a limited period” if they face “particular circumstances”, subject to the post-facto approval of the Commission. Article 13 obliges Member States to ensure that provisions of

EU data protection law dealing with judicial remedies, liabilities and sanctions apply to Member States' transposing measures. It also requires the punishment by “penalties, including administrative or criminal penalties, that are effective, proportionate and dissuasive,” of any illegal access to or transfer of retained data.

Article 14 obliged the Commission to undertake “an evaluation of the application of this Directive and its impact on economic operators and consumers” and present it to the European Parliament and the Council (see further below). Article 14 also obliged the Commission to determine at this time “whether it is necessary to amend the provisions of this Directive”, a decision that

the Commission has deferred, leaving no precise timetable for a new proposal.

Articles 15-17 require Member States to transpose the Directive into national law by 15 September 2007. Article 15(3) allows Member States to “postpone application of this Directive to the retention of communications data relating to Internet Access, Internet telephony and Internet e-mail” for up to three years. Austria, Belgium, Cyprus, Czech Republic, Estonia, Finland, Germany, Greece, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Poland, Slovenia, Sweden and the UK all took up this option. The national legislation through which Member States transposed the Directive is

listed in the EUR-Lex register.

Transposition and review

Nearly seven years after the deadline for implementation, the Directive has still not been implemented by all the states it covers and genuine “harmonisation” appears a remote prospect. Even with the extra room for manoeuvre on internet data retention, six Member States still found themselves subjected to infringement proceedings brought by the Commission after failing to implement national legislation on time.

The Commission brought proceedings against Austria, the Netherlands and

Sweden in May 2009, Greece and Ireland in November 2009, and Germany in May 2012. Austria,

Greece,

the Netherlands,

Ireland and

Sweden subsequently adopted legislation; Germany has failed to do so and an infringement action is pending at the European Court of Justice.

In Norway (obliged to implement the Directive through membership of the European Economic Area) legislation is yet to be agreed by parliament, and there is an on-going

campaign by civil society organisations against it. The Commission

recently demanded that Belgium “change its data retention laws to comply with the provisions of the European legislation”, and a

draft bill aimed at ensuring full implementation was introduced into the Belgian Parliament in July 2013.

The Commission's evaluation of the Directive, due in September 2010, was eventually

published in April 2011. It concluded that:

“[D]ata retention is a valuable tool for criminal justice systems and for law enforcement in the EU. The contribution of the Directive to the harmonisation of data retention has been limited, in terms of, for example, purpose limitation and retention periods, and also in the area of reimbursement of costs incurred by operators, which is outside its scope.”

Retention period and scope

That the Directive failed to harmonise retention periods is hardly surprising – it allowed Member States to choose from anywhere between 6 and 24 months. The failure of the Directive to define “serious crime” also led to wide divergences across Member States:

“Ten Member States (Bulgaria, Estonia, Ireland, Greece, Spain, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Hungary, Netherlands, Finland) have defined ‘serious crime’, with reference to a minimum prison sentence, to the possibility of a custodial sentence being imposed, or to a list of criminal offences defined elsewhere in national legislation. Eight Member States (Belgium, Denmark, France, Italy, Latvia, Poland, Slovakia, Slovenia) require data to be retained not only for investigation, detection and prosecution in relation to serious crime, but also in relation to all criminal offences and for crime prevention, or on general grounds of national or state and/or public security. The legislation of four Member States (Cyprus, Malta, Portugal, UK) refers to ‘serious crime’ or ‘serious offence’ without defining it.”

Most Member States also “allow the access and use of retained data for purposes going beyond those covered by the Directive, including preventing and combating crime generally and the risk of life and limb”.

Access to retained data

The authorities permitted to access retained data differ significantly from state to state. Every Member State allows police access and all except the UK and Ireland give access to prosecutors. 14 states provide access to security and intelligence agencies (only 12 are easily identifiable in the report – Bulgaria, Estonia, Spain, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Hungary, Malta, Poland, Portugal, Slovenia and the UK). Six (Finland, Hungary, Ireland, Poland, Spain, UK) give access to tax and/or customs authorities; and four to border police (Estonia, Finland, Poland, Portugal). The UK allows other public authorities access to data retained if “authorised for specific purposes under secondary legislation.”

The type of authorisation required for access is also uneven: “Eleven Member States require judicial authorisation for each request for access to retained data. In three Member States judicial authorisation is required in most cases,” but the information provided in the report is not specific enough to allow identification of these states. A senior authority, but not a judge, must give authorisation in four other Member States (five Member States' information – Cyprus, France, Hungary, Italy, Poland – appears to fit this description). In two Member States, “the only condition appears to be that the request is made in writing,” although the information provided indicates that three states have such systems: Ireland, Malta and Slovakia.

Legitimacy and effectiveness

The Commission has acknowledged that many groups and individuals consider mandatory data retention “in principle… unjustified and unnecessary”. Nevertheless, EU Home Affairs Commissioner Cecilia Malmström has

stated that “data retention is here to stay”. This has not allayed concerns about either the legitimacy or effectiveness of the Directive.

In May 2011 the European Data Protection Supervisor issued a

formal Opinion on the Commission’s evaluation report. Amongst other things, he said, the Commission needed to “invest in collecting further practical evidence from the Member States in order to demonstrate the necessity of data retention as a measure under EU law”, and that all those Member States in favour of data retention should prove “quantitative and qualitative evidence” demonstrating its necessity.

In December 2011 the European Commission wrote to the EU Council’s Working Party on Data Protection and Information Exchange (DAPIX) to inform Member States’ representatives of the results of the consultation that informed its April 2012 evaluation report. The Commission argued that it was necessary to “explain better the value of data retention” due to “a continued perception that there is little evidence at an EU and national level on the value of data retention in terms of public security and criminal justice”:

“We have received strong views from law enforcement and the judiciary from all Member States that communications data are crucial for criminal investigations and trials, and that it was essential to guarantee that these data would be available if needed for at least 6 months or at least… 1 year. We have also received strong qualitative evidence of the value of historic communications data in specific cases of terrorism, serious crime and crimes using the internet or by telephone – but only from 11 out of 27 Member States.”

Furthermore, “[t]he statistics required under Article 10 do not, as it is currently interpreted, enable evaluation of necessity and effectiveness”. Therefore, the Commission concluded, “all Member States – not just a minority – need to provide convincing evidence of the value of data retention of security and criminal justice”.

Member States’ delegations in DAPIX had already discussed the need for further evidence of the “necessity” of mandatory data retention at a meeting in May 2011. They concluded that retention:

“[C]ould not be argued on the basis of statistical data… the gravity of the offences investigated thanks to traffic data, rather than the mere number of cases in which traffic data were used should receive due attention. Quantitative analysis should be complemented with qualitative assessment."

In March 2013 the Commission published

a report that attempted to draw together “[e]vidence which has been supplied by Member States and Europol in order to demonstrate the value to criminal investigation and prosecution of communications data retained under Directive 2006/24/EC.” The report contains an overview of the ways in which communications data are used in criminal investigations and judicial proceedings; the sorts of cases in which retained data are important; the “consequences of absence of data retention”; and a section on statistics and quantitative data. This notes that 23 Member States have provided “some statistics since 2008”, but that they “interpret in different ways terms from the DRD such as ‘case’ and ‘request’, and statistics vary in format which limits their comparability”.

However, what the statistics do show is massive variation in the extent that Member States are using their data retention powers, with total annual requests ranging from 23 (Portugal) to 777,040 (UK).

In November 2012 – six years after the adoption of the Directive – the Commission adopted and disseminated “more comprehensive guidance on provision of statistics under Article 10”. Such problems meant that the majority of the Commission's March 2013 report (20 of 30 pages) was given over to anecdotal evidence, including 91 reported cases from across Europe in which retained data assisted in finding the perpetrators of a variety of serious crime.

Alternative approaches

“Data preservation” regimes offer an alternative to data retention, by limiting retention of data to specific authorised investigations. In November 2012 the European Commission published a

report it had commissioned on “current approaches to data preservation in EU Member States and third countries”. Data preservation was defined as the “expedited preservation of stored data or ‘quick freeze’” in:

“[S]ituations where a person or organisation (which may be a communications service provider or any physical or legal person who has the possession or control of the specified computer data) is required by a state authority to preserve specified data from loss or modification for a specific period of time”.

The report explained that data preservation is already mandated by the Council of Europe

Convention on Cybercrime (the Budapest Convention), which entered into force on 1 July 2004 and is open for worldwide signature. All EU Member States have signed the Convention although Greece, Ireland, Luxembourg, Poland and Sweden still need to ratify it (as of 7 April 2014). Under the Convention data may be preserved “for the purpose of specific criminal investigations or proceedings”.

The Convention, unlike the Data Retention Directive, explicitly permits the storage of communication content.

While the German Ministry of Justice believes that data preservation is fundamentally an alternative to mandatory retention, the report concludes that:

“[D]ata retention and data preservation are complementary rather than alternative instruments… data retention plays a role in ensuring that data is kept and that this is sometimes a prerequisite for data preservation, as data may have already been deleted before a data preservation order is issued.”

Revision of the Directive

Article 14 requires the European Commission to determine, on the basis of its review, whether it is necessary to amend the provisions of the Data Retention Directive. In August 2012 the

Commission announced that it was postponing the revision of the Data Retention Directive with “no precise timetable” for a new proposal. The Commission spokesperson cited the need to review the “e-Privacy” Directive to “ensure that retained data will be used exclusively for the purposes foreseen in this Directive, and not for other purposes as currently allowed by the e-Privacy Directive.”

Before the revision of either of these two Directives takes place, the Commission wants to see its draft data protection package agreed by the Council and the Parliament. At present the two institutions

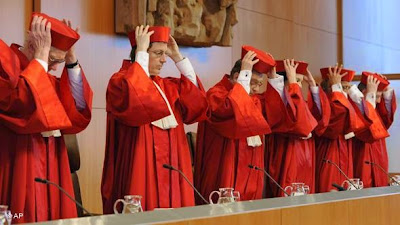

disagree significantly on the proposal, with further disagreement amongst the Member States in the Council. However, more fundamental to the future of the Directive may be today's judgment of the European Court of Justice.

Barnard & Peers: chapter 9, chapter 25