Professor Steve Peers

It’s nearly the end of this long

referendum campaign. If you’re still an undecided voter, or wavering about your

choice, or if you know someone who is either of those things, I’d like to set

out the arguments why I believe you should vote to stay in the European Union.

I’ll start out by setting out the

case for a Remain vote, then discuss the counter-arguments made by the Leave

side.

The case to Remain

In my view, there are a series of

reasons to stay in the EU: economic benefits, security, workers’ rights and the

environment. I’ll take each of these in turn.

Economic issues

EU membership gives the UK access

to the world’s biggest market, plus 50 more countries which the UK has trade

deals with via the EU. It might be possible to renegotiate that access from

scratch if we left the EU – but it might not. Why take the risk that it isn’t?

The only way to guarantee market

access to the EU and 50 other countries is a vote to Remain. So it’s no wonder

that the large

majority of British businesses support the UK’s EU membership, and are

worried about their prospects if we vote to Leave.

Loss of that guaranteed market

access wouldn’t just affect those whose jobs are linked to trade with the EU. It

would also affect the broader economy, due to the impact on investment and because

the government would have less to spend on public services in a smaller economy.

Many people are suspicious of

economic forecasts. But the risks of a Brexit vote have already manifested themselves

in the last few weeks. The value of the pound and stock markets (which include

pension assets) dropped when a Leave vote seemed more likely, and increased

again when the odds of a Remain vote went back up. There are reports of capital

flight from the country. There’s surely a reason that the Bank of England has

drawn up crisis

plans in the event of a Leave vote – but no such plans in the event of a

Remain vote.

Let’s look further at those

economic forecasts. It’s true that many forecasters failed to predict the 2008

crash. But one who did, Nouriel Roubini, has also warned of

the economic effects of a Leave vote. And the forecasting record of the few

economists on the Leave side is not great either: Patrick Minford predicted

that the UK would lose millions of jobs when the minimum wage was first introduced.

In fact, it’s striking to note

that some pro-Brexit economists also

predict less economic growth for some time following Brexit, although they have

no reason to lie about that – just the reverse. Andrew Lilico expects less

economic growth until 2030:

And Patrick Minford argues that

Brexit can only work if the UK mostly

eliminates manufacturing – hardly a pleasant prospect for British

workers in manufacturing jobs, and their families and communities.

Security

EU membership comes with a host

of laws regarding police and criminal law cooperation. As I discuss here,

those laws have helped the UK get hold of far more fugitives for trial in the

UK, and also remove more criminals for trial abroad. The amount of data

exchanged between police services on alleged terrorists or other criminals has

increased too. Moreover, the UK’s justice system is not threatened by EU law in

this field: we have an opt-out which the government has frequently used.

Countries outside the EU have

access to only a small fraction of these EU measures, and there would be legal

complications if the UK sought to renegotiate access to police data exchange

after Brexit. There’s clear proof of this – even a non-EU country like the USA has

faced repeated legal and political challenges trying to obtain such access in

practice.

Again, the only way to guarantee being

part of these laws is a vote to Remain – while a vote to Leave would remove the

UK from much of this cooperation between police and prosecutors.

Workers

Despite some attempts to deny it,

it’s clear (as I discuss in detail here)

that EU laws have increased the level

of protection for workers’ rights – including equal treatment of women in the workplace – above the level

it would otherwise be in the UK. 60% of EU cases involving equal treatment of

women in the UK, and 62% of other EU cases involving workers’ rights in the UK,

have led to increased protection.

These rulings have improved

rights as regards (among other things) pregnant workers and maternity leave,

equal pay for work of equal value, paid holidays for more workers, and the

protection of occupational pensions when an employer goes broke. It’s no wonder

that the large

majority of trade unions support the UK’s EU membership.

Many senior figures on the Leave

side have explicitly admitted they want to scrap these protections. Indeed,

Nigel Farage says that women who have had children are ‘worth less’ to their

employers. So, again, the only way to guarantee these rights is a vote to

Remain. A Leave vote would risk the future of these employment and equality law

protections, by putting their fate in the hands of people who are implacably

opposed to them.

Environment

There is a raft of EU laws protecting

the environment: from air pollution, to clean beaches, to nature protection,

among many more. It’s no wonder that the Green party and environmental NGOs support the UK’s

EU membership.

On the other side, the pro-Brexit

environment minister has admitted

that there are many EU environmental laws he would scrap in the event of a

Brexit. The businesses backing the Leave side have drawn up a hit list of dozens of environmental

laws they want to rip up.

So, again, the only way to

guarantee these rights is a vote to Remain. As with workers’ rights, a Leave

vote would hand over environmental protection in this country to those who have

admitted their intention to reduce protection.

What about the case to Leave?

What are the risks to Remain?

The Leave side have argued that

there are a number of risks to remaining in the EU. As I point out in detail here,

these arguments are unfounded. The UK has a veto over tax laws, defence,

foreign policy, future enlargement of the EU, the basics of the EU budget

(including the EU rebate), trade deals with non-EU countries (including the

controversial planned ‘TTIP’ deal with the USA), and transfers of powers to the

EU. Turkey is not about to join the EU:

it has agreed only one out of 35 negotiating chapters in 11 years of

negotiations. The UK has an opt out from the single currency, bail outs of Eurozone

states, joining Schengen and EU asylum and criminal law.

You may not trust British politicians

to keep these safeguards. But in the large majority of cases, it’s not up to

them to decide on that – it’s up to us, the voters. British law already says

that in the case of any transfer of powers to the EU, including the creation of

an EU army or joining Schengen or the single currency, another referendum would

be needed to approve the decision, as well as our government and parliament

voting in favour.

Economic

Is there an economic case to

leave the EU? It’s true that the EU has common rules on trade with non-EU

countries, so the UK would in theory be able to sign separate trade deals with

those countries where the EU has not done a deal yet.

The problem is that this theory

would be hard to put into practice. As discussed in detail here,

the UK would have to start from scratch negotiating trade deals with those

non-EU countries which already have a trade deal with the UK, via the EU.

(These include the majority of Commonwealth countries, as I discuss here).

Some of these EU-wide trade deals are very advantageous to the UK – for instance

our exports to Korea have hugely

increased since the EU trade deal with that country. The head of the World Trade Organisation has

also warned

that this would be a difficult task.

In the meantime, the UK would

have to renegotiate access to its largest trading partner – the EU. It’s true

that both sides would have an economic interest in such a deal. But nevertheless,

trade deals take years to negotiate, either with the EU or non-EU countries. There

are plenty of cases where a deal is never struck at all, despite the economic

interests on both sides.

Moreover, the Leave side say they

want a free trade deal with the EU, not continued participation in the EU’s

single market. That doesn’t bode well for the UK’s trade with the EU after Brexit,

because (as explained here)

a single market gives better access to services markets – and the UK has a big

net surplus in services exports.

When asked about economic issues,

those on the Leave side have often said ‘I don’t know’ or ‘so what’. Some have

expressed indifference to a negative impact a Leave vote might have on the

economy, or said that an economic downturn is a ‘price worth paying’ for leaving

the EU.

A good example of this attitude was

Nigel Farage’s attitude in one of the debates to the pharmaceutical industry – a

huge

UK employer (see the graph) with big net exports to the rest of the EU. He was indifferent to

what might happen to this industry if the UK left the EU, referring to the UK’s

‘domestic market’ and ‘alternative medicine’ instead.

While Boris Johnson has promised

to apologise if leaving the EU causes a recession, that would be cold comfort

to anyone losing their job. The Leave side has no coherent economic plan for

what happens after a Leave vote and appear indifferent to the prospect of

economic loss if we leave.

On a related point, it’s true

that the UK is indeed a net contributor to the EU budget. But the Leave side

has exaggerated the amount the UK pays. As discussed here,

the British rebate money is never sent to the EU, and the UK has control over

the EU money that it sent back to the UK. In all, the net contribution is 1% of

public spending, or 12p per day for the average taxpayer:

That amount of money will not

save the NHS or end austerity. Anyway, as the independent Institute of Fiscal

Studies has pointed

out, even a small drop in economic growth as a result of Brexit would have

a much bigger impact for the UK government’s budget – and therefore taxpayers –

than the UK budget contribution to the EU.

Sovereignty

The Leave side have argued that

the UK needs to leave the EU to be a ‘sovereign’ country. But as pointed out here,

decisions on new EU laws aren’t made by EU Commissioners, but by elected

ministers from each EU country and elected Members of the European Parliament.

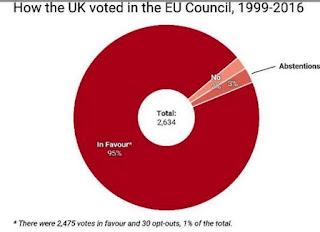

Moreover, the UK has voted in favour of 95% of EU legislation:

As for the proportion of UK laws

which come from the EU, the House of Commons has estimated that it’s

only 13%. That doesn’t include EU regulations, but as pointed out here,

most EU regulations aren’t laws in the ordinary sense, but administrative

decisions. So if you counted also all the administrative decisions made in the

UK as well (like every approval of longer pub opening hours, or home extension),

the proportion of British laws coming from the EU would still be small.

Anyway, the key test for

sovereignty is not the percentage of UK laws that come from the EU, but the

percentage of UK laws that were imposed on the UK against our will by the

EU. It’s ridiculous to say that UK laws which were already on the

books, or which we agreed to change at the same time as other Member States, are

an invasion of sovereignty.

Applying this test, since the UK voted

for 95% of EU law, the percentage of UK law imposed against the UK’s will is

only 5% of those 13% of national laws which come from the EU – or 0.65% of the

statute book. Even if you believe the claims of some on the Leave side that 60%

of UK laws come from the EU, the percentage of our laws that were imposed

against our will by the EU would only be 3%. So the sovereignty issue has

simply been hugely exaggerated by the Leave side.

Immigration

The Leave side have argued

against the level of immigration to the UK. But as I have pointed out in detail

here,

the majority of those coming to the UK are non-EU citizens, where the UK

controls the numbers. That’s demonstrated by this graph:

EU law does govern the number of

EU citizens who come to the UK. But they can’t stay unless they have a job or

are self-sufficient. The UK can (and does) deny them social benefits until they

have worked here for a time; and the UK’s renegotiation deal will allow us to

deny them key in-work benefits as well. The UK can (and does) expel or refuse

entry to EU citizens who pose a security risk or who have a criminal record too.

Non-EU citizens do try to enter

the UK from the EU, but they would do that even after Brexit, since it wouldn’t

alter the law in any way on this point. In fact, after Brexit the UK would no

longer be part of the EU’s Dublin system for sending asylum-seekers back to other

EU countries, so in some respects migration control would be harder, not

easier.

There’s a clear trade-off between

EU migration and the economic benefits of EU membership. As the Leave side

points out, countries like Norway and Switzerland are wealthy outside the EU.

But they’ve also signed up to free movement of people with the EU, and have a

greater share of migrants in their population than the UK does.

Is there a left-wing case to leave the EU?

Some on the left-wing side of

British politics believe there is a left-wing case to leave the EU (a so-called

‘Lexit’). There’s an obvious flaw in their logic: there’s no ‘Lexit’ box on the

ballot paper. A Brexit vote tomorrow would not deliver a left-wing government

to office. Rather, as Owen Jones,

Paul

Mason and George

Monbiot have pointed out, it would shift power to those on the right wing

of the Conservative party who favour austerity and loathe

the NHS.

Although, as noted above, those

same people have announced

their intention to scrap environmental and employment laws after Brexit, Lexit

supporters plan to rely on the kindness of Tories to protect those rights. Never

in the course of human history have so many left-wingers had so much faith in

their traditional opponents – with so little reason to do so. If you want a

vision of the future after Brexit, imagine Iain Duncan-Smith fist-punching –

forever.

Conclusion

Of course, the UK has many problems.

But the question is, which of those problems would actually be solved by leaving the EU? Our EU

contribution accounts for 1% of public spending, and EU laws which we didn’t

vote for make up a tiny proportion of our statute book.

Rather, it was our government that

decided to implement austerity cuts. Our government decided to reorganise the

NHS. Our government brought in a bedroom tax, and planned cuts to disability benefits,

while cutting income tax for high earners. Our government nearly tripled

university tuition fees (in England). Our government reduced trade union

rights, hiked industrial tribunal fees, and encouraged zero-hour contracts –

and sets the level of the minimum wage.

Our government sets rates of

income tax, national insurance contributions, inheritance tax and company tax,

and controls what local governments charge as council tax. EU law sets minimum

rates of VAT and excise tax, but the government voted for those laws (it has a

veto on EU tax law), and anyway our government has set the rate of those taxes

well above the EU minimum.

Our government decides on how

much to spend on pensions, on other benefits, on the NHS, on schools, on roads,

on housing, and on foreign aid – on everything except the 1% of the government

spending that goes to the EU. Our national debt stems from our government’s

decisions on how much to spend, compared to how much to tax.

Simply put, our government

controls nearly every decision that affects the UK, including the majority of migration

to the UK. There’s no point voting to Leave based on any of those decisions

which are within our country’s control.

The case to Remain in the EU is

that it enhances our country’s strengths. Membership gives us a guarantee of

trade with our largest market, and 50 other countries besides. It guarantees

continued cooperation on policing and criminal law, and continued protection of

workers’ and environmental rights.

Outside the EU, there are no

guarantees – only risks. The economic risks that trade and investment are

reduced. The security risks that we have less cooperation with police and

prosecutors in the EU. The social and environmental risks of fewer protections

for workers and the environment.

And this would all be for an

illusory gain of sovereignty: when our EU contribution accounts for 1% of

public spending; when we vote for 95% of EU laws; when at most 3% of our laws

were imposed upon the UK against its will by the EU. In effect, the Leave side

want to cut down a forest because they don’t like one tree.

The best way to ensure economic

growth, while retaining other benefits of EU membership, with only marginal

impact on our sovereignty, is to vote to Remain in the EU.

Photo credit: newlovetimes.com

Excellent article, best work I have read during this debate. It's a shame that the remain politicians couldn't make these points last night on BBC. They were very poor if you ask me, and really missed the boat all bluster. If more people read this blog, the remain vote would be in the bag by now.

ReplyDeleteNice read, one question. You mention EU regulations that are not necessarily laws. What kinds of things might they be?

ReplyDeleteThanks. Those would be things like the Regulations setting the daily price of fruit and vegetable imports.

DeleteGreat article, thanks Steve

ReplyDeleteInteresting read. But, the EU needs to be involved in 'Regulations setting the daily price of fruit and vegetable imports' why?

ReplyDeleteIt's not regulating the retail price, it's regulating in terms of the common agricultural and commercial policy. Every country in the world has some sort of restriction on agricultural imports to protect their farmers.

Delete