Professor Justin Borg-Barthet, University of Aberdeen*

*Advisor to a coalition of press freedom NGOs on the

introduction of SLAPPs, co-author of the CASE Model Law, lead author of a study

commissioned by the European Parliament, and member of the Commission's Expert

Group on SLAPPs and its legislative sub-group

Background

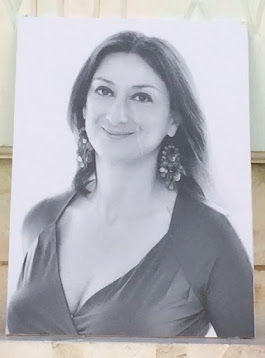

When Daphne Caruana Galizia was

assassinated in Malta on 16th October 2017, 48

defamation cases were pending against her in Maltese and other courts. Daphne

was at the peak of her journalistic powers when she was killed, producing a

seemingly endless exposé of criminality involving government and private sector

actors. Naturally, those she was exposing did not take kindly to the intrusion

on the enjoyment of the fruits of their labour. Courts which offered few

meaningful safeguards against vexatious litigation presented a nominally legitimate

forum in which they would seek to exhaust and punish Daphne and to ensure that

others did not engage in similar investigations. Most of these cases were

inherited by her sons, whose grief was interrupted constantly by a need to

appear in court in defence of their mother’s work.

The scale of abusive litigation

which Daphne endured prompted several NGOs to look more closely at the

phenomenon of SLAPPs. Strategic Lawsuits Against Public Participation, a term

coined in American academic circles, are lawsuits intended not to serve the

legitimate purpose of pursuing a claim against a respondent, but instead to use

court procedure to suppress scrutiny of matters of public interest. The direct

costs, psychological strain, and opportunity costs of defending oneself in

court are intended to coerce retraction of legitimate public interest activity,

and to have a chilling effect on others who might show an interest. While most

SLAPPs are framed as defamation claims, there is also a growing body of abusive

litigation which suppresses public participation using the pretext of other

rights such as privacy and intellectual property.

In response to the growing SLAPP

phenomenon, several

US States, Canadian provinces and Australian states and territories have

introduced anti-SLAPP statutes. Typically, these statutes provide for the

early dismissal of cases, and include cost-shifting measures to compensate

SLAPP victims and to dissuade claimants. No EU Member State has yet adopted

similar laws. Prompted by Daphne’s experience, European NGOs and MEPs became

increasingly aware of the alarming incidence of SLAPPs throughout Europe. They

then set out to identify and advocate for legal solutions in the European

Union.

Initially, the European

Commission resisted calls for the introduction of anti-SLAPP legislation, citing

a lack of specific legal basis. As the legal and statistical research bases

for NGO advocacy evolved further, and following a change

in the Commission’s political leadership, the Commission’s assessment

changed. This culminated in the introduction of a package

of anti-SLAPP measures on 27th April 2022, including a proposed anti-SLAPP

Directive which Vice-President Jourova dubbed “Daphne’s Law”.

The legislative proposal is

based, in part, on a Model

Law which was commissioned by the Coalition Against SLAPPs in

Europe (CASE), a grouping of NGOs established to further the research basis

and advocacy for anti-SLAPP laws in Europe. That Model Law is itself inspired

by anti-SLAPP statutes adopted in the United States, Canada and Australia, but accounts

for divergent continental legal traditions, and benefits from extensive

consultation with experts and practitioners in Europe and elsewhere.

Legal Basis and Scope

As noted above, the key barrier

for NGOs and MEPs to persuade the Commission to initiate anti-SLAPP legislation

was disagreement about whether the EU had competence to act in this area. Subsequently,

however, the Commission recognised the internal market relevance of SLAPPs, as

well as adopting a more strident approach

to the rule of law and human rights implications of SLAPPs. Arguments

concerning a legal basis included an approach based

on numerous treaty articles (as in the Whistleblowers’

Directive), reliance on the internal market effects of SLAPPs (Article 114

TFEU) as in the Model Law, and the potential use of treaty

provisions on cross-border judicial cooperation. Ultimately, in view of

Member States’ expected resistance to intervention in domestic procedural law, the

Commission’s draft proceeds on the basis that Article 81 TFEU confers

competence in respect of judicial cooperation in civil matters.

The orthodox view of Article 81 TFEU

presupposes an international element to matters falling within its scope. It

was therefore incumbent on the drafters to constrain the scope of the proposed

directive to cases having a cross-border dimension. The Commission’s proposal

begins with a classic private international law formulation which refers to the

domicile of the parties. A case lacks cross-border implications if the parties

are both domiciled in the Member State of the court seised. This, however, is

subject to a far-reaching caveat in Article 4(2):

Where both

parties to the proceedings are domiciled in the same Member State as the court

seised, the matter shall also be considered to have cross-border implications

if:

a)

the act of public participation concerning a

matter of public interest against which court proceedings are initiated is

relevant to more than one Member State, or

b)

the claimant or associated entities have

initiated concurrent or previous court proceedings against the same or

associated defendants in another Member State.

The Commission’s proposal adopts

an innovative formulation, the breadth of which is commensurate to the internal

market and EU governance implications of SLAPPs. Given the EU’s interconnectedness,

it is paramount that the law account for the fact that cross-border

implications do not flow only from the circumstances of the parties but also from

transnational public interest in the underlying dispute.

The broad scope could be extended

further if and when Member States come to transpose the proposed directive in

national law. It is hoped, and indeed recommended

as good practice, that Member States will take the view that national transposition

measures will not be restricted to matters falling within the scope of the

Directive but would apply also to purely domestic cases. This would avoid the

prospect of reverse discrimination against SLAPP victims in domestic disputes.

It would also minimise opportunistic litigation concerning the precise meaning

of ‘[relevance] to more than one Member State’ in Article 4(2)(a).

Defining SLAPPs

Other than in the title and

preamble, the proposed directive does not deploy the term ‘SLAPPs’. Discussions

preceding the drafting process noted a number of difficulties associated with

the term, not least (i) its unfamiliarity to a European legal audience, and (ii)

the potential confusion resulting from the word ‘strategic’, which could be

understood to require evidence of said strategy. In keeping with the Model Law,

the Commission’s draft Directive deploys familiar language and focuses on the abusive

nature of the proceedings. Rather than referring to SLAPPs, therefore, the text

of the draft directive uses the term ‘abusive court proceedings against public

participation’.

In identifying matters falling

within the scope of the draft directive, it is first necessary to establish

that a matter concerns ‘public participation’ on a matter of ‘public interest’.

The Commission’s draft accounts for the fact that SLAPPs do not only target

journalistic activity, but also seek to constrain legitimate action of civil

society, NGOs, academics, and others. Public participation and public interest

are therefore defined broadly as follows in Article 3:

‘public

participation’ means any statement or activity by a natural or legal person

expressed or carried out in the exercise of the right to freedom of expression

and information on a matter of public interest, and preparatory, supporting or

assisting action directly linked thereto. This includes complaints, petitions,

administrative or judicial claims and participation in public hearings;

‘matter of

public interest’ means any matter which affects the public to such an extent

that the public may legitimately take an interest in it, in areas such as:

a)

public health, safety, the environment, climate

or enjoyment of fundamental rights;

b)

activities of a person or entity in the public

eye or of public interest;

c)

matters under public consideration or review by

a legislative, executive, or judicial body, or any other public official

proceedings;

d)

allegations of corruption, fraud or criminality;

e)

activities aimed to fight disinformation;

If a case concerns public

participation in matters of public interest, it is then necessary to establish

that the proceedings are abusive in accordance with the definition in Article

3:

‘abusive court

proceedings against public participation’ mean court proceedings brought in

relation to public participation that are fully or partially unfounded and have

as their main purpose to prevent, restrict or penalize public participation.

Indications of such a purpose can be:

a)

the disproportionate, excessive or unreasonable

nature of the claim or part thereof;

b)

the existence of multiple proceedings initiated

by the claimant or associated parties in relation to similar matters;

c)

intimidation, harassment or threats on the part

of the claimant or his or her representatives.

There are therefore two key

elements to the notion of abuse: (i) claims may be abusive because they are

fully or partly unfounded, or (ii) they may be abusive because of vexatious tactics

deployed by claimants. The implications of a finding of abusiveness will vary

depending on the type of abuse identified in the proceedings, with more robust

remedies available where the claim is manifestly unfounded in whole or in part.

Main legal mechanisms to combat SLAPPs

Once a court has established that

proceedings constitute SLAPPs falling within the directive’s scope, three key

remedies will be available to the respondent in the main proceedings: (i) the

provision of security for costs and damages while proceedings are ongoing, (ii)

the early dismissal of proceedings, and (iii) payment of costs and damages.

Speedy dismissal of claims is

considered the cornerstone of anti-SLAPP legislation. Accelerated dismissal

deprives the SLAPP claimant of the ability to extend the financial and

psychological costs of proceedings to the detriment of the respondent. Early

dismissal of cases must, of course, be granted only with great caution given it

is arguable that this restricts the claimant’s fundamental right to access to

courts. The solution provided in the draft directive is to restrict the

availability of this remedy to claims which are manifestly unfounded in whole

or in part. It is for the claimant in the main proceedings to show that their

claim is not manifestly unfounded (Art 12).

Early dismissal is not available

where the claim is not found to be manifestly unfounded, even if the its main

purpose is ‘to prevent, restrict or penalize public participation’ (as

evidenced by ‘(i) the disproportionate, excessive or unreasonable nature of the

claim…the existence of multiple proceedings [or] intimidation, harassment or

threats on the part of the claimant’). This differs from the Model Law which

envisages early dismissal in cases which are not manifestly unfounded but which

bear the hallmarks of abuse. The Model Law’s authors reasoned that a court should

be empowered to dismiss a claim which is designed to abuse rather than

vindicate rights. This would not, in our view, constitute a denial of the right

to legitimate access to courts but would dissuade behaviour which is

characterised as abusive in the Commission’s own draft instrument. While the

Commission’s reasoning and caution are understandable, the high bar set by the

requirement of manifest unfoundedness allows for significant continued abuse of

process.

This shortcoming is mitigated

somewhat by the other remedies, namely the provision of security pendente lite (Article

8) and liability for costs, penalties, and compensatory damages (Articles

14-16), which are available regardless of whether the SLAPP is manifestly

unfounded or merely characterised by abuse of rights. These financial remedies

are especially useful insofar as they give the respondent some comfort that

they will be compensated for the loss endured through litigation. They are also

expected to have a dissuasive effect on SLAPP claimants who would be especially

loathe to the notion of rewarding the respondent whose legitimate exercise of

freedom of expression they had sought to dissuade or punish. Nevertheless, it

bears repeating that in all cases these remedies, designed to compensate harm,

should supplement the principal remedy of early dismissal which is intended to prevent

harm.

In addition to these main devices

to dissuade the initiation of abusive proceedings against public participation,

the draft directive includes a number of further procedural safeguards. These

include restrictions on the ability to alter claims with a view to avoiding the

award of costs (see Recital 24 and Article 6), as well as the right to third

party intervention (Article 7) which will enable NGOs to submit amicus briefs

in proceedings concerning public participation. While this may appear to be a

minor innovation at first blush, it could have substantial positive

implications insofar as it would equip more vulnerable respondents (and less

expert courts) with valuable expertise and oversight.

London Calling: Private International Law Innovation

While the provisions discussed

above would limit the attractiveness of SLAPPs in EU courts, there would remain

a significant gap if EU law did not provide protection against the institution

of SLAPPs in third countries. London, with its high litigation costs and somewhat

claimant friendly defamation laws, is an especially

attractive forum for claimants who wish to suppress public scrutiny. Equally,

other States could be attractive to claimants who wish to circumvent EU

anti-SLAPP law, whether simply as a function of the burden of transnational

litigation, or because of the specific content of their substantive and/or

procedural laws. The draft directive therefore proposes to introduce harmonised

rules on the treatment of SLAPP litigation in third countries.

Article 17 provides that the recognition

and enforcement of judgments from the courts of third countries should be

refused on grounds of public policy if the proceedings bear the hallmarks of

SLAPPs. While Member States were already empowered to refuse recognition and

enforcement in such cases, the inclusion of this article ensures that protection

against enforcement of judgments derived from vexatious proceedings is

available in all Member States.

Article 18 provides a further

innovation by establishing a new harmonised jurisdictional rule and substantive

rights to damages in respect of SLAPPs in third countries. The provision confers

jurisdiction on the courts of the Member State in which a SLAPP victim is

domiciled regardless of the domicile of the claimant in the SLAPP proceedings. This

would provide an especially robust defence against the misuse of third country

courts and reduce the attractiveness of London and the United States as venues

from which to spook

journalists into silence.

While the limitation of forum

shopping in respect of third countries is, of course, welcome, there does

remain a significant flaw insofar as EU law and the Lugano Convention facilitate

forum shopping within the European judicial area. The cumulative effect of EU

private international law of defamation is to provide mischievous litigants

with ample opportunity to deploy transnational litigation as a weapon to suppress

freedom of expression. NGOs

have therefore requested amendment of two EU private international law

instruments:

In the first

instance, and as a matter of urgency, the Brussels I Regulation (recast)

requires amendment with a view to grounding jurisdiction in the domicile of the

defendant in matters relating to defamation. This would remove the facility for

pursuers to abuse their ability to choose a court or courts which have little

connection to the dispute;

The omission

of defamation from the scope of the Rome II Regulation requires journalists to

apply the lowest standard of press freedom available in the laws which might be

applied to a potential dispute. We recommend the inclusion of a new rule which

would require the application of the law of the place to which a publication is

directed;

These changes have not yet been

forthcoming. It is hoped that ongoing reviews of these instruments will yield

further good news for public participation in the EU.

Concluding remarks

Daphne’s Law will now have to be

approved by the Council of Ministers and the European Parliament. The legislative

process may see a Parliament seeking more robust measures pitted against Member

States who may be inclined to protect their procedural autonomy. The Commission

has considered these competing demands in its draft and sought to propose

legislation which strikes a balance between divergent institutional stances. Nevertheless,

it must be expected that the draft will be refined as it makes its way through

the approval process. As noted above, the draft would be improved if those

refinements were to include the extension of early dismissal to cases beyond

the narrow confines of manifest unfoundedness. Equally, the draft directive

should be viewed as a first welcome step in the pushback against SLAPPs in

Europe and that reviews of private international law instruments will follow

soon after.

Photo credit: ContinentalEurope,

on Wikicommons