Lorna Woods, Professor of Internet Law, University of Essex

Yesterday’s Advocate-General’s opinion

concerns two references from national courts which both arose in the aftermath

of the invalidation of the Data Retention Directive (Directive 2006/24) in Digital

Rights Ireland dealing with whether the retention of communications

data en masse complies with EU law. The

question is important for the regimes that triggered the references, but in the

background is a larger question: can mass retention of data ever being human

rights compliant. While the Advocate General clearly states this is possible,

things may not be that straightforward.

Background

Under the Privacy and Electronic Communications Directive (Directive

2002/58), EU law guarantees the confidentiality of communications

transmitted via a public electronic communications network. Article 1(3) of that Directive limits the

field of application of the directive to activities falling with the TFEU,

thereby excluding matters covered by Titles V and VI of the TEU at that time (e.g.

public security, defence, State security).

Even within the scope of the directive, Article 15 permits Member States

to restrict the rights granted by the directive

‘when such restriction constitutes a

necessary, appropriate and proportionate measure within a democratic society to

safeguard national security, defence, public security, and the prevention,

investigation, detection and prosecution of criminal offences or of

unauthorised use of the electronic system..’.

Specifically, Member States were permitted to legislate for

the retention of communications data (ie details of communications but not the

content of the communication) for the population generally. The subsequent Data

Retention Directive specified common maximum periods of retention and

safeguards, and was implemented (in certain instances with some difficulty) by

the Member States.

Following the invalidation of the Data Retention Directive,

the status of Member State data retention laws was uncertain. This led both

Tele2 and Watson (along with a Conservative MP, David Davis, who withdrew his

name when he became a cabinet minister) to challenge their respective national

data retention regimes, essentially arguing that such regimes were incompatible

with the standards set down in Digital

Rights Ireland. The Tele2 case

concerned the Swedish legislation which implemented the Data Retention

Directive. The Watson case concerned

UK legislation which was implemented afterwards: the Data Retention and Investigatory Powers Act (DRIPA). Given this

similarity, the cases were joined.

The Swedish reference asked whether traffic data retention

laws that apply generally are compatible with EU law, and asked further

questions regarding the specifics of the Swedish regime. Watson et al asked two questions: whether the reasoning in Digital Rights Ireland laid down

requirements that were applicable to a national regime; and whether Articles 7

and 8 of the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights (EUCFR) established stricter

requirements than Article 8 of the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR) –

the right to private life. Although the latter case concerns the UK, the Court’s

will still be relevant if the UK leaves the EU because the CJEU case law

provides that non-Member States’ data protection law must be very similar to EU

data protection law in order to facilitate data flows (see Steve Peers’

discussion here).

Opinion of the Advocate

General

The Advocate General dealt first with the question about the

scope of the protection under the EUCFR.

This question the Advocate General ruled as inadmissible because it was

not relevant to resolving the dispute. In

so doing, he confirmed that the obligation in Article 52 EUCFR to read the

rights granted by the EUCFR in line with the interpretation of the ECHR

provided a base line and not a ceiling of protection. The EU could give a higher level of

protection; indeed Article 52(3) EUCFR expressly allows for the possibility of

‘… Union law providing more extensive protection’.

Moreover, Article 8 EUCFR, in providing a specific right to

data protection, is a right that has no direct equivalent in the ECHR; the

Advocate General therefore argued that the rule of consistent interpretation in

Article 52(3) EUCFR does not apply to Article 8 EUCFR (Opinion, para 79). Later

in the Opinion, the Advocate General also dismissed the suggestion that Digital Rights Ireland did not apply

because the regime in issue in Watson et

al was a national regime and not one established by the EU legislature.

Articles 7, 8 and 52 EUCFR were interpreted in Digital Rights Ireland and are again at issue here: Digital Rights Ireland is therefore

relevant despite the different jurisdiction of the court (paras 190-191).

The Advocate General then went on to consider whether EU law

permits Member States to establish general data retention regimes. The first question was whether Article 1(3)

meant general data retention regimes were excluded from the scope of Directive

2002/58 because the sole use of the data was for the purposes of national security

and other grounds mentioned in Art 1(3).

The Advocate General made three points in response:

Given that Article 15(1) specifically

envisaged data retention regimes, national laws establishing such a regime were in fact implementing

Article 15(1) (para 90).

The argument the governments put

forward was related to the access to the data by public authorities, the

national schemes concerned the acquisition and retention of that data by

private bodies – that the former might lie outside the directive did not imply

that the latter also did (paras 92-94).

The approach of the Court in Ireland v Parliament and Council (Case

C-301/06), which was a challenge to the Data Retention Directive as regards

the Treaty provision on which it was enacted, meant that general data retention

obligations ‘do not fall within the sphere of criminal law’ (para 95).

The next question was whether Article 15 of the Directive applied.

The express wording of Article 15, which refers to data retention, makes clear

that data retention is not per se

incompatible with Directive 2002/58. The intention was rather to make any such

measures subject to certain safeguards. This means that data retention can be

legal provided the scheme complies with the safeguards (para 108). Indeed, following

his earlier reasoning, the Advocate General rejected the argument that Article

15 is a derogation and should therefore be read restrictively.

This brings us to the question of whether sufficient

safeguards are in place. Since the Advocate General took the view that in

providing for general data retention regimes the Member States are implementing

Article 15, such measures fall within the scope of EU law and therefore,

according to Article 51 EUCFR, the Charter applies, even if rules relating to

access to the data by the authorities lie outside the scope of EU law (paras

122-23). Nonetheless, given the close

link between access and retention, constraints on access are of significance in

assessing the proportionality of the data retention regime.

Assessing compliance with the EUCFR requires as a first step

an interference with rights protected. The Advocate General referred to Digital Rights Ireland to accept that

‘[g]eneral data retention obligations are in fact a serious interference’ with

the rights to privacy (Art 7 EUCFR) and to data protection (Art. 8 EUCFR) (para

128). Justification of any such interferences must satisfy both the

requirements set down in Article 15(1) Directive 2002/58 AND Article 52(1)

EUCFR which sets out the circumstances in which a member State may derogate

from a right guaranteed by the EUCFR (para 131). The Advocate General then

identified 6 factors arising from these two obligations (para 132):

Legal basis for retention;

Observe the essence of the rights in

the EUCFR (just Article 52 EUCFR, rather than Art 15 of the directive);

Pursue an objective of general

interest;

Be appropriate for achieving that

objective;

Be necessary to achieve that

objective; and

Be proportionate within a democratic

society to the pursuit of the objective.

As regards the requirement for a legal basis the Advocate

General argued that the ‘quality’ considerations that are found in the ECHR

jurisprudence should be expressly applied within EU law too. They must have the

characteristics of accessibility, foreseeability and providing adequate

protection against arbitrary interference, as well as being binding on the

relevant authorities (para 150). These factual assessments fall to the national

court.

In the Opinion of the Advocate General, the ‘essence of the

rights’ requirement – as understood in the light of Digital Rights Ireland – was unproblematic. The data retention

regime gave no access to the content of the communication and the data held was

required to be held securely. A general interest objective can also easily be

shown: the fight against serious crime and protecting national security. The

Advocate General, however, rejected the argument that the fight against

non-serious crime and the smooth running of proceedings outside the criminal

context could constitute a public interest objective. Likewise, data retention

gives national authorities ‘an additional means of investigation to prevent or

shed light on serious crime’ (para 177) and it is specifically useful in that

general measures give the authorities the power to examine communications of

persons of interest which were carried out before they were so identified. They

are thus appropriate.

A measure must be necessary which means that ‘no other

measure exists that would be equally appropriate and less restrictive’ (Opinion,

para 185). Further, according to Digital

Rights Ireland, derogations and limitations on the right of privacy apply

only insofar as strictly necessary. The

first question was whether a general data retention regime can ever be

necessary. The Advocate General argued that Digital

Rights Ireland only ruled on a system where insufficient safeguards were in

place; there is no actual statement that a general data retention scheme is not

necessary. While the lack of differentiation was problematic in Digital Rights Ireland, the Court ‘did

not, however, hold that that absence of differentiation meant that such

obligations, in themselves, went beyond what was strictly necessary’ (Opinion,

para 199). The fact that the Court in Digital Rights Ireland examined the

safeguards suggests that the Court did not view general data retention regimes

as per se unlawful. (see also Schrems (Case C-362/14), para 93, cited here in

para 203). On this basis the Advocate General opined:

a general data retention obligation need not invariably be

regarded as, in itself, going beyond the bounds of what is strictly necessary

for the purposes of fighting serious crime. However, such an obligation will

invariably go beyond the bounds of what is strictly necessary if it is not

accompanied by safeguards concerning access to the data, the retention period

and the protection and security of the data. (para 205)

The comparison as to the effectiveness of this sort of

measure with other measures must be carried out within the relevant national

regime bearing in mind the possibility that generalised data retention gives of

being able to ‘examine the past’ (para 208). The test to be applied, however,

is not one of utility but that no other measure or combination of measures can

be as effective.

The question is then of safeguards and in particular whether

the safeguards identified in paras 60-68 of Digital

Rights Ireland are mandatory for all regimes. These rules concern:

Access to and use of retained data by

the relevant authorities;

The period of data retention; and

The security and protection of the

data while retained.

Contrary to the arguments put forward by various governments,

the Advocate General argued that ‘all the safeguards described by the Court in

paragraphs 60 to 68 of Digital

Rights Ireland must be regarded as mandatory’ (para 221, italics in

original). Firstly, the Court made no mention of the possibility of

compensating for a weakness in respect of one safeguard by strengthening

another. Further, such an approach would no longer give guarantees to

individuals to protect them from unauthorised access to and abuse of that data:

each of the aspects identified needs to be protected. Strict access controls

and short retention periods are of little value if the security pertaining to

retained data is weak and that data is exposed. The Advocate General noted that

the European Court of Human Rights in Szabo

v Hungary emphasised the importance of these safeguards, citing Digital Rights Ireland.

While the Advocate General emphasised that it is for the

national courts to make that assessment, the following points were noted:

In respect of the purposes for which

data is accessed, the national regimes are not sufficiently restricted (only

the fight against serious crime, not crime in general, is a general objective)

(para 231)

There is no prior independent review

(as required by para 62 Digital Rights

Ireland) which is needed because of the severity of the interference and

the need to deal with sensitive cases (such as the legal profession) on a case

by case basis. The Advocate General did accept that in some cases emergency

procedures may be acceptable (para 237).

The retention criteria must be

determined by reference to objective criteria and limited to what is strictly

necessary. In Zacharov,

the European Court of Human Rights accepted 6 months as being reasonable but

required that data be deleted as soon as it was not needed. This obligation to

delete should be found in national regimes and apply to the security services

as well as the service providers (para 243).

The final question relates to proportionality, an aspect

which was not considered in Digital

Rights Ireland. The test is:

‘a measure which interferes with

fundamental rights may be regarded as proportionate only if the disadvantages

caused are not disproportionate to the aims pursued’ (para 247).

This opens a debate about the importance of the values

protected. In terms of the advantages of the system, these had been rehearsed

in the discussion about necessity. As regards the disadvantages, the Advocate

General referred to the Opinion in Digital

Rights Ireland, paras 72-74 and noted that

‘in an individual context, a general

data retention obligation will facilitate equally serious interference as

targeted surveillance measures, including those which intercept the content of

communications’ (para 254)

and it has the capacity to affect a large number of people. Given

the number of requests for access received, the risk of abuse is not

theoretical. While it falls to the

national courts to balance the advantages and disadvantages, the Advocate

General emphasised that even if a regime includes all the safeguards in Digital Rights Ireland, which should be

seen as the minimum, that regime could still be found to be disproportionate

(para 262).

Comment

It is interesting that the Court of Appeal’s reference did

not ask the Court whether DRIPA was compliant with fundamental rights in the

EUCFR. Rather, the questions sought to close off that possibility – firstly by

limiting the scope of the EUCFR to a particular conception of Article 8 ECHR

and secondly by seeking to treat Digital Rights Ireland as a challenge to the

validity of a directive as not relevant within the national field. Although the Advocate General did not answer

the first question, the reasons given for dismissing it make clear that the

Court of Appeal’s approach was wrong. Indeed, it is hard to see how Art 52(3)

when read in its entirety could support the argument that the EUCFR should be

‘read down’ to the level of the ECHR. The entire text of Article 52(3) follows:

In so far as this Charter contains

rights which correspond to rights guaranteed by the Convention for the

Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms, the meaning and scope of

those rights shall be the same as those laid down by the said Convention. This

provision shall not prevent Union law providing more extensive protection.

The focus of the second question was likewise misguided. As

the Advocate General pointed out, Digital

Rights Ireland was based on the interpretation of the meaning of two

provisions of the EUCFR, Articles 7 and 8.

They should have the same meaning wherever they are applied.

Quite clearly, the Advocate General aims to avoid saying that

mass surveillance – here in the form of general data protection rules – is per

se incompatible with human rights. Indeed, one of the headline statements in

the Opinion is that ‘a general data retention obligation imposed by a Member

State may be compatible with the fundamental rights enshrined in EU law’ (para

7). The question then becomes about reviewing safeguards rather than saying

there are some activities a member State cannot carry out. This debate is common in this area, as the

case law of the European Court of Human Rights illustrates (see Szabo, particularly the dissenting opinion).

Fine distinction abound. For example, where the Advocate

General relies on the distinction between meta data and content to reaffirm

that the essence of Article 7 and 8 has not been undermined. Yet while the Advocate General tries hard to

hold that general data retention may be possible, tensions creep in. The point the Advocate General made in

relation to the ‘essence of the right’ was based on the assumption that meta

data collection is less intrusive than intercepting content. In assessing the impact of a general data

protection regime, the Advocate General then implies the opposite (paras

254-5). Indeed, the Advocate General quotes Advocate General Cruz Villalon in Digital Rights Ireland that such

surveillance techniques allow the creation of:

‘a both faithful and exhaustive map

of a large portion of a person’s conduct strictly forming part of his private

life, or even a complete and accurate picture of his private identity’.

The Advocate General here concludes that:

‘the risks associated with access to

communications data (or ‘metadata’) may be as great or even greater than those

arising from access to the content of communications’ (para 259).

Another example relates to the scope of EU law. The Advocate

General separates access to the collected data (which is about policing and

security) and the acquisition and storage of data which concerns the activities

of private entities. The data retention regime concerns this latter group and

their activities which fall within the scope of EU law. In this the Advocate

General is following the Court in the Irish judicial review action challenging

the legal basis of the Data Retention Directive (the outcome of which was that

it was correctly based on Article 114 TFEU).

The Advocate General having separated these two aspects at the question

of scope of EU law, then glues them back together to assess the acceptability

of the safeguards.

In terms of safeguards, the Advocate General resoundingly

reaffirms the requirements in Digital

Rights Ireland. All of the

safeguards mentioned are mandatory minima, and weakness in one area of

safeguards cannot be offset by strength in another area. If the Court takes a

similar line, this may have repercussions for the relevant national regimes,

for example as regards the need for prior independent review (save in

emergencies). Indeed, in this regard the Advocate General might be seen to

going further than either European Court has.

Further, the Advocate General restricts the purposes for which general

data retention may be permitted to serious crime only (contrast here, for

example, the approach to Internet connect records in the Investigatory

Powers Bill currently before the UK Parliament).

Another novelty is the discussion of lawfulness. As the Advocate

General noted, there has not been much express discussion of this issue by the

Court of Justice, though the requirement of lawfulness is well developed in the

Strasbourg case law. While this then might be seen not to be particularly new

or noteworthy, the Advocate General pointed out that the law must be binding

and that therefore:

‘[i]t would not be sufficient, for

example, if the safeguards surrounding access to data were provided for in

codes of practice or internal guidelines having no binding effect’ (para 150)

Typically, much of the detail of surveillance practice in the

UK has been found in codes; as the security forces’ various practices became

public many of these have been formalised as codes under the relevant

legislation (see e.g. s. 71 Regulation of

Investigatory Powers Act; codes available here).

Historically, however, not all were publicly available, binding documents.

While the headlines may focus on the fact that general data

retention may be acceptable, and the final assessment of compliance with the 6

requirements falls to the national courts, it seems that this is more a

theoretical possibility than easy reality. The Advocate General goes beyond

endorsing the principles in Digital

Rights Ireland: even regimes which satisfy the safeguards set out in Digital Rights Ireland may still be

found to be disproportionate. While Member States may not have wanted to have a

checklist of safeguards imposed on them, here even following that checklist may

not suffice. Of course, this opinion is not binding; while it is designed to

inform the Court, the Court may come to a different conclusion. The date of the

judgment has not yet been scheduled.

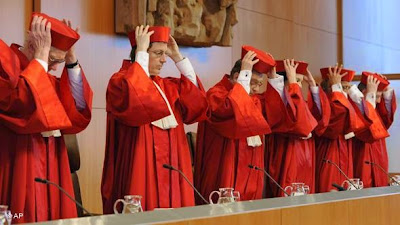

Photo credit: choice.com.au

Barnard & Peers: chapter 9

JHA4: chapter II:7